"The Spitz will be exterminated!"

The story of a US American character assassination

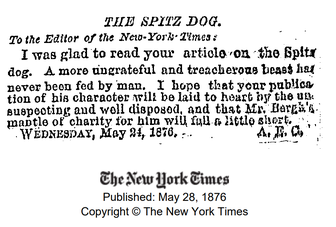

On May 24, 1876, the white German Spitz fell from favor in the United States. At that time, an article appeared in the New York Times with the ominous title "A Whited Canine Sepulcher". In this article, the author apparently exposes the "true" character of the Spitz and ultimately cannot avoid calling for the eradication of the Spitz, blaming it for cases of rabies and distemper. See the NYT article here:

The Spitz is exposed

Dog dealers once imported the German Spitz to America. It is generally assumed - and you can read it everywhere - that German immigrants brought the Spitz with them, but this is rather unlikely, as most immigrants of that time were extremely poor (most of them left their home countries due to their poverty), and therefore they probably had no way of feeding a dog.

The May 1876 article noted that the Spitz was rarely found in America until twenty years ago, but that it has now become so widespread that "it is almost worthless in the dog market." On November 17, 1876, another report mocking the German Spitz confirmed that they were once fashion dogs and were imported. This article went so far as to suggest punishment for anyone who continued to import the breed, as well as the slaughter of all those already in the country.

The purpose of “exposing” the Spitz was to show the public that the Spitz dog has a predisposition to spreading rabies. Although the author makes it clear that he was not a fanatic or hater of the Spitz and that he found his leadership role very unpleasant, and he even apologized to his friends for his article, he still saw it as his duty to the public to inform them of the character of the Spitz. To reveal secrets, just like you would expose a criminal. The white Spitz - a "beast" who mingled with the best circles of society - was, in the journalist's opinion, a wolf in sheep's clothing. The author of the article totally humanizes the Spitz and transfers human character traits to the dog; so, with regard to morality, he wrote that "the Spitz is incorrigibly corrupt through and through" and "a tireless and shameless thief." He was said to have skills that enabled him to steal the bones of “honest dogs” slyly and without a guilty conscience. The Spitz also had a cunning and treacherous face and was also extremely vain and devious: it attacked and bit when its victims least expected it and fled when challenged, even from children.

In "A Whited Canine Sepulcher" it is claimed that the breed caused 75% of the city's deaths due to hydrophobia. This is what a symptom of rabies was called - among other things, the victims are typically afraid of water and cannot swallow, hence the water phobia. Although there was a lack of hard evidence, the article blamed Spitzes for a variety of deaths, including the recent death of a young girl. A few years earlier, Francis Butler had died of the disease. He was apparently caring for a sick Spitz when he was bitten. He died six weeks later.

Rabies

Rabies was not a disease of epic proportions back then. The mortality rate following a bite from a rabid dog was apparently 1 in 15 (NY Times, July 7, 1874) and there were an average of 3.75 rabies deaths per year. At that time, nearly 6,000 people died annually from diarrheal diseases, while an average of 9,000 children died annually in the damp and moldy tenements of New York. It is therefore astonishing that an increase in hydrophobia victims from 3.75 cases to 5 or 6 per year was noticed so dramatically. The medical profession also had reasonable doubts that all the victims were actually real cases.

So in 1874, doctors wondered why so few deaths were enough to send Brooklyn and New York crazy with fear. The medical profession was already talking about a condition that became known as pseudo-hydrophobia or hysterical disorder, in which the victim lived in such fear of the disease that he died of seizures of fright. This hysteria was suspected, among others, in Francis Butler. The seizures have also often been suspected as a result of intemperance, tetanic convulsions (a result of tetanus), meningitis, and so on.

At that time, Spitz only had to look askance or express mild displeasure to be declared rabies. This led to the dogs starting to be beaten to death in the streets. The hysteria took on ever more bizarre proportions, so that more and more charlatans were up to mischief. A man claimed to have cured his son of rabies with a "magic stone" now worth $50. A doctor at Presbyterian Hospital in New York "cured" a teenager who mistakenly believed he had hydrophobia by tying him to the bed and beating him with a wooden splint (normally, this was used to splint broken bones). An older doctor said: “It is a miracle that we are still alive, as afraid as we are of everything.”

When in November 1876, after the deaths of two German men - they lived in a shack on 68th Street and died of hydrophobia - whose Spitzes were blamed for their deaths, an article appeared in the New York Times entitled "A Venomous Beast". It listed the four most poisonous animals in the United States, which were: the rattlesnake, the North American copperhead, the moccasin viper and the Pomeranian (yes, really...), which, according to the journalists, had set out to end humanity by infecting humanity with hydrophobia to eradicate. Um yeah...sure! As a result of this article, Spitzes in the United States were massively persecuted for several years, often beaten to death, poisoned or shot by a panicked audience.

Meanwhile, an ordinance was passed by the city authorities to solve the general problem of stray dogs. Previously, in 1874, the city passed a law that proved to be a shot in the arm, because by offering a 50 cent reward for each stray turned in to the shelter, a veritable epidemic of dog thefts soon ensued. Because half a dollar was a lot of money back then.

A regulation from 1877 generally required that all dogs on public streets be accompanied by a human and be on a dog collar and leash. There was some kind of tax stamp hanging from the collar. All dogs that were not on a leash or caught without a tag were allowed to be caught and killed by the dogcatcher (the original says "punished by death").

The destruction of the German Spitz

In June 1877 another article (“The Dog Law”) appeared that called for an attack on the Spitz. There, Spitzes were equated with murderers who only had a malicious grin for the gallows because they have supposedly bitten without the slightest fear of punishment. The article concludes by saying that the Spitz needs to be confronted, if only to show the Spitz that he is not above the city government. Here, too, the Spitz is unfortunately humanized, much to its detriment! A man named Mr. Bergh was tasked with coming up with a suitable "death penalty" - but he had to choose the most humane method. This is despite Mr. Bergh having so many other charming ideas, like either smothering the Spitz with carbon dioxide or blowing it up with dynamite! The article says that the Spitzes only raised their proud rods in contempt at these threats from the "oh so kind-hearted" Mr. Berghs, because they apparently were of the opinion that they couldn't be killed in that way.

Anyone who previously found this really disturbing will now be disabused: the article “Destroying the Dogs” was published on July 6th. This article is written very graphically and is difficult for modern people to bear. Essentially, an iron cage measuring two meters long, four meters high and five meters wide was built and 759 adult dogs and 23 puppies were locked in units of 48 animals and then drowned in the river for ten minutes to become. A large crowd had gathered to witness the killing of the dogs. Twenty dogs deemed valuable were spared. The carcasses were taken to a nearby rendering plant and the hides were valued at one dollar each. Of course, there were a lot of poor Spitzes among the dogs. The article ends with another rant about Spitz dogs, as out of 48 men bitten, 39 were bitten by Spitz dogs. By the way, there are no reports if any of these men became infected with rabies. A later popular theory was that because dogcatchers were bitten so often, they were immune to rabies. However, it shows the rarity of true rabies, as it is unlikely that they were immune.

Beginning on April 28, 1878, the city of Long Branch banned Spitz dogs and required citizens and marshals to kill any Spitz spotted within city limits.

The Spitz is being rehabilitated

At the same time, worldwide dog shows began to emerge from this point on, including the upcoming second annual "Westminster Kennel Club Show" on April 28, 1878. Apparently, some people had tried to exhibit their Spitzes there, but this was rejected. The events concerning the Spitz in the U.S. did not miss the attention of cynologists and dog lovers in the rest of the world and Vale Nicholas wrote about the Spitz in his contribution to the "Kennel Encyclopaedia" in 1907: "In America the superstition was deeply rooted that they (the Spitz) were special were susceptible to rabies, so that for a year or two after 1880 no Spitzes were accepted at the New York dog Show." In fact, the refusal of entry took place before 1880. Rawdon Lee (1894) writes of the Spitz: "Some years ago there was a mad dog panic in New York, and in some places the origin is said to be traced to the Spitz dogs, many of which were destroyed without any Evidence has been provided."

Harrison Weir wrote an article in the London Standard in 1889, picked up by the New York Times in October, that discussed rabies: "I have been told that the Spitz is an unpredictable dog and is not allowed in some countries."

The Westminster Kennel Club held an inaugural exhibition limited to a few select sporting dog breeds. The exhibition was a complete success and inspired by this, the club decided to open its exhibition to other breeds too. The response was great, wealthy breeders sent entries by steamer and even two $20,000 collies were imported for exhibition directly from the Queen of England's kennels! This was supposed to be a big social event. The crème de la crème of American dog lovers should exhibit or participate. The last thing the club needed was mass hysteria caused by the mere presence of a German Spitz. Understandably, Spitzes were therefore banned from the exhibition. It wasn't until 1894 that a Spitz dog would be exhibited again at the "Westminster Kennel Club Show".

Victoria of England and the Pomeranian

Meanwhile, a trend developed in England to import small Spitzes from Germany and Italy and in the "Dreikaiserjahr" (Year of the Three Emperors) in 1888, no less a personality than the Queen of England was interested in the small, trendy "Toy Spitzes". Queen Victoria probably did more for the rehabilitation of Spitz in America than any other person. In November 1894, there was an article in the New York Times about their dogs, which described Gina as a 7½ pound Toy Spitz from Italy and introduced Marco (weighing 12 pounds) as the finest Pomeranian in England. Toy Spitzes became increasingly popular in the 1880s, with writers praising their friendly nature and good temperament - so it's no wonder they were liked! In the entire press, there was not a word of criticism of the Queen's Spitzes!

The society ladies of New York discovered their passion for the tiny Toy Pomeranians and made them a "must-have". Beginning in the late 1890s, English breeders exported their Spitzes and enormous sums of money changed hands. The Giant Spitz, on the other hand, was never fully accepted by the American dog show exhibitors, even after his return from his involuntary rabies exile to the exhibition ring; the aversion apparently ran too deep. The smaller size, on the other hand, particularly appealed to women, who were also gaining more and more influence in the ranks of the dog world.

The fact that the children of the future King George V were photographed with their Spitzes also ensured their rehabilitation in America. Actresses like Ellen Terry were seen in postcards hugging her white Pomeranian. Pictures often showed them doing tricks or performing in circuses. Audiences loved them - there are hundreds of postcards of various sizes and types that date from this period.

Further evidence that the race was being virtually rehabilitated came in 1905 with the publication in the NY Times of a light-hearted poem sent to the editor. It was about a German named Fritz with a German dog – his Spitz. Fritz said he was a good dog who never bit, and it was only the dog's temperament that affected him, not hydrophobic seizures. This time there was no editorial comment!

Unfortunately, in 1908 there was a second outbreak of rabies among New York residents! This time, however, the New York Times very sensibly urged the public to remain calm and be fair to the dogs. They pointed out that there are no facts to support the recent concerns. This was, in fact, a change of heart on the part of the newspaper after it noted that the Times had first alerted the public to the connection between Spitz dogs and rabies, thus starting the craze.

This time, Spitz dogs were not persecuted or fell out of favor. In fact, an article in another newspaper criticized the NY Times for being the first to rally the public against the Spitz, calling its story "a case of newspaper hydrophobia."

Conclusion

In addition to the fact of these incredible events, another exciting fact is revealed here: the curtain on the hidden past of the "Eskie" is lifted a little. It seems that the renaming from "German Spitz" respectively "American Spitz" to "Eskimo Dog" is not only due to anti-German sentiment during the world wars, but may also have been done to get rid of the stigma of the rabid Spitz dog of the late 19th century only attached to the Spitz - but not to the American Eskimo Dog. From this perspective, the name change was a smart move. Since no source provides any other, somewhat satisfactory explanation for how the imported German Spitz became the American Eskimo Dog, this could be a possible explanation here.

Another important aspect that must be seen here: the misperception of the breed-specific characteristics of the Spitz by the public at the time. Here, historical evidence of a tendency toward snappishness was clearly overstated and exaggerated, just as natural characteristics of the breed were misinterpreted as signs of madness and illness. Behavioral disorders such as epilepsy or hysteria were also - as was proven in the 1940s - sometimes caused by chemical substances that were previously used in the production of flour, which was then also used in dog biscuits and dry food. Also, there was and is no clear evidence at all that the white Spitzes were more susceptible to rabies. Our breed is different from many other dog breeds, but they are not dangerous.

Queen Victoria with Spitz bitch Gina (note the floppy right ear - which probably didn't even bother a queen back then!)

24.08.2021