The German Spitz - an ancient farm dog

Germany has an ancient farm dog breed, the German Spitz. He is a born house and farm dog and is inextricably linked to his master's property.

However, anyone who speaks or hears of a farmer's dog usually thinks of a breedless mutt that, poorly or not cared for at all, fed on bones and scraps of bread, eke out h his chained to a miserable hut. Unfortunately, this is often the case. However, a farmer's dog was by no means understood everywhere as an inferior mixed breed; in Central Europe, Spitzes, Hovawarts and Pinschers were most commonly found as guardians of the farm. These animals have always been very alert, weatherproof and frugal, yet clever and easy to train. And the last-mentioned quality was the most important for the farmer.

In this respect, the cynologist Rudolf Löns rightly stated:

“If the farmer had to devote as much time and effort to training as the modern dressage books prescribe, then the dog would not be a help to him, but a new burden.”

What the farmer demands from the dog, vigilance, loyalty to the house and a certain sharpness, the dog should have, so to speak, at birth. That doesn't mean that the farmer doesn't train him at all, but that he just doesn't have to teach him in a great and elaborate way. What the farmer's dog was always taught, however, was to refuse food: only an incorruptible guard dog is a reliable guard dog.

Taking the dog along to farm field work was a nice thing for the dog because it gave him a chance to get some exercise, but it had the disadvantage that it excited the hunting appetite of many dogs and turned many honest household member into an incorrigible poacher. In medieval Germany, in the "Heiligen Römischen Reich Deutscher Nation" (Holy Roman Empire), hunting was an exclusive prerogative of the nobility. If farmers or ordinary citizens kept dogs that were able to hunt, these dogs had to be made unsuitable for hunting, for example by chopping off a leg or by having them wear a thick wooden stick around their neck. However, since the farmers needed their dogs for house and farm work, herding work and a number of other operation areas - something that simply cannot be managed with a crippled dog - the nobility's request could not be implemented in the long term (even economically). Finally, a particular breed of dog, namely the Spitz, was selected so that it practically no longer had any hunting drive Such a Spitz without any poaching drive was finally allowed by the nobility to be used as a house and farm dog by the farmers:

"Darnach kleine oder mittelmäßige Hündlein, die man das nachts auf der Stube und auf dem Hof hat, dass sie unser (!) und unserer Nahrung Wechter seyn". (“The small or medium-sized dogs that you have in the room and on the farm at night are guards for us (!) and our food.") [1]

Mistbella - the dunghill barker

These “Spitz-like” dogs appeared in the Middle Ages with a variety of functions. As already mentioned, the tasks of this dog breed were very diverse, on the one hand they were guards of the house and the farm and were used as herding dogs, on the other hand they were also used as lapdogs. In rural areas the breed was not always known as “Spitz”, but was instead referred to as “Mistbella” or “Mistbeller”. [8th]

This classic dunghill, on which the Spitz preferred to sit, formed a welcome perch from which he could easily monitor all entrances to the farm. In addition, the dung heap warmed him from below in the winter.

The centuries-old connection between Spitz and man has given the German Spitz all the skills that make him indispensable, especially for agriculture. He is a true all-rounder: he guards, herds and drives the cattle, he destroys vermin and is also a brilliant family dog and kindergarten teacher for the little ones. He also has no inclination to hunt or stray.

It is important to emphasize at this point that only the German Spitz has the special characteristic of lacking a hunting drive - all of its foreign relatives are still often used for hunting today. And the Spitz is born with all his watchdog abilities, which is why, even in modern times, there has never been anything like a working test for him as part of the breeding approval.

Guard dogs, like the Spitz, were so existential to people that they were even buried in rituals as so-called "Bauopfer" (building sacrifices) to ward off harm, which points to their relevance as guardians of house and yard. Many building victims can be found from the early Middle Ages: dogs were buried in post pits or under the doorstep - as symbolic house guards. However, it is often unclear whether the dogs were killed specifically for this purpose or whether animals that had already died were buried this way. This rite was preserved, albeit less frequently, into the High and Late Middle Ages and partly into the early modern period. An example is the discovery of such a sacrificial dog at the Ketzelburg in Haibach, which was built in the 12th century.

Spitz = barn Hound?!

About the German Spitz as ancient farm dog Pietro de' Crescenzi tells us in his 13th century AD written book about agriculture about the German Spitz. He provides lots of clues in IX. book, 87th chapter which is about the dogs. The farm dog forms at that time were:

- The farm dog, referred to as "Hovawarth " in Alemannic law and in the "Lex Baiuvariorum" as early as the 8th century;

- the "Barnbracke" (barn Hound);

- the “Mistbeller” or “Mistbella”.

Crescentiis tells us that the names "Barnbracke/ barn Hound" and "Mistbeller" were synonymous. What now, a Hound a farm dog??? 😲 Yes, actually:

- Barn = barno (Old High German) = crip

- Bracke = brakko (Old High German) = dog, hunting dog

What was meant was a dog that guarded the barn, the crib, a barn dog. "Mistbella" or "Mistbeller" was a dog that barked on the dunghill, therefore also a barn dog. And as we already know, the term "Mistbella" meant the Spitz (see above). The meaning of the word Bracke = hound also provides us with a decisive clue to the predatory nature of the farm dogs of the time, because what is a "crip hunting dog" (Barnbracke) other than a dog that hunts vermin in the barn? And who hunts vermin very successfully? Right, it's our Spitz!

Nowadays, "Barn Hunt" is recognized as a dog sport by the American Kennel Club. The purpose of this sport is that the dog must find all the rats hidden in the tunnels on the competition area faster than the other dogs. This competition area looks like a barn.

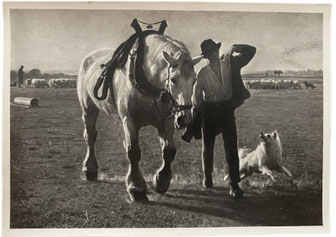

The Wolfspitz, the traditional farm dog

Of all the Spitz varieties, the Wolfsspitz is the basic form, which was certainly available to farmers in its familiar form many centuries (or millennia) ago. There is something primal and respectable about Wolfspitzes. They are excellent, weatherproof guardians and defend their master's property with courage and fearlessness. The dense, easy-care fur is silver-gray, with black guard hairs, the small ears are pointed, standing upright, and the eyes are clever and intelligent. They are tough fellows and like no other breed, they have been predestined as farming dogs for centuries, also because, in addition to their guarding duties, they are excellent at herding livestock - the dog's oldest purpose, according to Buffon. Until a few decades ago, the large Wolfspitz dogs in Germany were even approved for police dog examination - that diverse are they! It was not without reason that Brehm wrote that the German Spitz means the same thing for the house and farm as the German Shepherd Dog means the shepherd. The large Spitz was the extended arm of the farmer, just as the sheepdog was the extended arm of the shepherd.

The shape of the skull makes the difference

The fact that the Wolfspitz is probably the oldest representative of the German Spitz can also be seen in the shape of its skull: As part of the domestication of the wolf, the skull also changed, resulting in a type of juvenile regression in dogs, the so-called paedomorphosis. The dog basically remained at the stage of an adolescent, which is reflected in his appearance. But the domestic dog skull itself has also been subject to more or less major changes (depending on the duration of domestication).

Domestic dog skulls differ from wild dog skulls primarily in that the highest point of their profile is never the occipital protuberance, but rather that this is usually close behind the orbital ring (the eye socket). This is where the profile bends. The forehead and snout parts slope down to varying degrees from this break point. In more primitive dog breeds, such as the Wolfspitzes and many pariah dogs, the profile remains stretched: the bridge of the nose from the orbit to the nasal foramen (nasal bone) is straight, not sunken. However, the other German Spitz breeds differ significantly from the Wolfspitz breeds in terms of their skull structure, because their skulls already show more of the characteristics of the domestic dog and have much more youthful shapes that are somewhat similar to the child's pattern. The forehead and snout parts are clearly set apart (the so-called “stop”), which recedes from the forehead part. The orbit is straight.

The Wolfspitz is ancient, the Keeshond is not

What that means? That we can clearly distinguish two groups within the German Spitz population, also based on the shape of the skull: those of the Wolfspitzes and those of the other Spitz varieties. The Wolfspitz is much more reminiscent of the wild canids, both in terms of coat color and the shape of his skull, than the Giant, Mittel and Miniature Spitz - although it can be assumed that the Wolfspitz and the other Spitzes ultimately have a common origin. [5]

The Wolfspitz, in its actual, original form, is actually an ancient guardian of the German homeland. How old is already evident from its primitive skull shape. However, the Wolfsspitz is in no way to be equated with a modern, breeding variety of his breed, namely the Keeshond. This not only has a more juvenile skull shape - i.e. is much younger in terms of developmental history - but also lacks any working characteristics. Only and exclusively the German Wolfsspitz in its original form is worth protecting - as an old German cultural asset!

The centuries-long partnership between the farmers and the Wolfspitz has given him the working qualities that make him so valuable and indispensable, especially in the house, farm and field. The Wolfspitz is not only an excellent guardian who gets along particularly well with all farm animals, but he is also excellently suited to being a herding dog. With amazing confidence he finds lost livestock and rounds them up. If possible, he only touches the cattle with his muzzle, but without grabbing it. He even goes so far as to safely guard and lead the herd entrusted to him, even without humans, and bring them to pasture and back home.

"By barking and nipping, she (the Wolfspitz bitch, author's note) ensures that the cows always walk in a row and don't stray. She knows exactly the times. She is sent from the house to fetch the cows so that they can be milked. Furthermore, she guards them during milking and leads them back to the pasture after milking." (from "Der Tierfreund" no. 9/1965).

The guard dog as the helper of modern man

No other pet species achieves the diversity found in domestic dogs. And no other domestic animal is as different from its original species, the wolf, as the dog. The use of dogs has always been an essential contribution to the survival of an entire habitat and therefore a fundamental prerequisite for human development and existence. Without guard dogs, there would be no livestock farming (presumably the development of livestock farming would not have been possible without the cooperation of dogs), no field farming protected from foreign predators and no guarded and defended private property, which forms the basis of our society today. The guard dog - and with it the ancient farmer and herding dog Spitz - is of existential importance for the development of today's Central European people. It can be assumed that the dog has made such a massive contribution to human evolution that it may not have existed without his help. How would people be today if the farm, wagon, crops and livestock had remained without effective and inexpensive protection from dogs?

The dog was therefore highly respected by most prehistoric cultures, such as the Indians, the Assyrians, the ancient Egyptians and the ancient Germanic peoples. The Awesta, the holy scripture of the Zoroastrian religion, already points out the great importance of the watchdog for human development:

"For the dwellings would not stand firmly on the earth created by Ahura if it were not for the dogs that belong to the cattle and the village."

And in this sense the God (Ahura) in the Vendidad himself said to his prophet Zoroaster:

"I have created the dog, with his own clothes and his own shoes, with a pungent smell and sharp teeth, attached to man, for protection of the herds; I have created the dog, with a vicious body for the enemy. When he is healthy, when he is with the herds, when he is in a good voice, then no thief or wolf comes to the village and carries away goods unnoticed." [2]

The dog as a companion, not as an accessory

Old dog breeds such as the Spitz were an essential help in the triumph of modern humans, which is unthinkable without them. Unfortunately, the characteristics of the Spitzes, which have been valued over thousands of years, are now only partially in demand or even desired, but are rather perceived as annoying. Just a few decades ago, the German Spitz was praised for his eager yapping and sharpness, but today this behavior is a reason for a serious neighbor dispute or even the termination of the apartment. Today's absolute claim to power by humans leaves no room for other creatures. However, the role of a living, only tolerated stuffed animal/accessory/sports equipment/prestige object cannot be a perspective for the old comrade dog, which is more closely linked to humans than any other animal.

Unfortunately, we humans often forget the origins of our four-legged companions and why they are the way they are. Instead, we often try every means possible to train the animals out of the behavior that has been bred deeply into them over many generations. However, this does not do justice to the great role of dogs in human history. So dear people, please appreciate our German Spitz again, because he has always been the real guardian of the farms and should be allowed to stay that way he is without having to be "modernized"! He deserves that and nothing else.

Sources:

- [1] "Verzeichnis der Wirbelthiere Oberschwabens" - Richard Freiherr König-Warthausen

- [3] Avesta, German by Spiegel, p. 200

- [5] "Untersuchungen am Schädel des Haushundes", Walter Frhr. Taets v. Amerongen,

- [7] Bielenbergstraße 8 in Kiel

- [8] Frömmel Monika: "Aspekte der sozialen Funktion von Hunden im Mittelalter", Wien 1999

- "Die im Regierungsbezirke Schwaben vorkommenden Säugethiere" by André Wiedemann

- Gray: "Notes of the skull of the Species of Dogs, Wolves and Foxes in the Collection of the British Museum". London, 1868

- Vendidad, 13. Fargard, verse 106-113

- "Über die Abstammung des Haushundes": L. H. Jeitteles

- Magister Johannes Pauli: "Schimpf und Ernst" from 1515

- Petrus de Crescentiis: "Ruralia commoda - Das Wissen des vollkommenen Landwirts um 1300"

07.11.2023