German Spitz or American Eskimo Dog?

About the differences between the two breeds

1.) Preface

There are still differing opinions about the rewriting of the American Eskimo Dog (also “Eskie” or “AED”) as a white Giant Spitz. I have already tried to solve whether the German Spitz and the American Eskimo Dog are the same dog breed or not (see "The American Eskimo Dog"). At that time, I came to the conclusion that although Eskies have their ancestry back to the Giant Spitz, they have since evolved into a different dog breed. In the meantime, I have new facts that I would like to point out here and that speak absolutely against converting the Eskie to a Large Spitz - provided there are no conditions attached - or mating both breeds without professional breeding control.

2.) The diversity-study

In May 2021, a study called “Genetic Diversity Testing for American Eskimo Dog” was released by Felipe Avila and Shayne Hughes. The Veterinary Genetics Laboratory (VGL) in collaboration with Dr. Niels C. Pedersen examined the genetic heterogeneity of the participating Eskies. The following emerged from this study (strongly summarized):

(A) The Eskies are no better off genetically than the Giant Spitz

The standard sized American Eskimo Dogs (38 – 50 cm) are in no better situation when it comes to their genetic diversity than the Giant Spitz. These Eskies, like many other “unpopular” breeds, have low genetic diversity and are relatively inbred. The number of DLA1 and DLA2 haplotypes identified in this study group was quite low compared to other breeds. The results of the study ultimately show that the AED breed was bred from a smaller number of founder animals and that these closely related lines were never truly outcrossed over time.

The study also comes to the following conclusion: If it were to be considered for the American Eskimo Dogs to increase the genetic diversity of the breed through outcrossing, the DNA of the dogs intended for this purpose would also have to be examined very carefully to ensure that the introduction of Genetic defects, illnesses, etc. can definitely be ruled out.

Result for us:

The results of the study allow us to draw the following conclusions: namely, that rewriting Eskies to Giant Spitzes and mating them with each other makes no sense at all. Or even just brings some kind of advantage to the large Spitzes. Because inbreeding x inbreeding still equals inbreeding. Outcrossing with foreign breeds only makes sense if the new breed being bred with is healthy.

The study's note that the dogs through whose introduction one would like to increase the genetic diversity of a breed must be examined very carefully in advance must be emphasized here! If the two imported Eskie bitches had been thoroughly examined in advance, the Giant Spitz population, for example, would have been spared the eye disease prcd-PRA (progressive retinal atrophy).

Click on the image for the study “GENETIC DIVERSITY TESTING FOR AMERICAN ESKIMO DOG”

3.) Differences in gait and body structure between Spitz and Eskie

In the American standards of the American Eskimo Dog, you can read that it is a trotting breed [4] - a breed that can trot for long periods of time without getting tired. The standards also say that his tendency to a sustained trot is reflected in his well-angled fore and hindquarters; with a tendency to "single track" as soon as its speed increases.

What that means? As the speed increases, the Eskie runs in a single track: the legs begin to gradually angle inwards until the pads land in a straight line directly under the longitudinal center of the body. During this movement the topline remains strong, level and firm. [3]

The opposite of the “single track” is the “double track”. Our German Spitz double tracks at higher speeds, unlike the Eskie. The breed standard for the German Spitz also requires a different angle of the hindquarters and a different back line than the American Eskimo Dog can have. I will now look at these differences in more detail:

3.1) The Eskie single tracks while the German Spitz double tracks

Land predators, such as the wolf, "single track" when trotting, which means that when they reach forward with their hind foot, they place it directly in the path of their forefoot. The track then basically looks like a continuous string of lined up footprints. When trotting, the hindquarters are in the same plane as the forequarters.

👉🏻 When it comes to the term “single tracking” - which is in German "schnüren" - the German hunter's language used the everyday language of the ancient Germans. The word “Schnur” - noun of "schnüren" that can be translated into the English term "cord" - originally referred to the daughter-in-law and meant the young woman who follows in her mother-in-law’s footsteps. Just like the Wolf steps into his previous footsteps.

• Old High German: Snur

• Middle High German: Snuor

The contrast to single tracking is “double tracking”. Here, the individual steps are more or less far away from the imaginary center line. In the case of particularly full-fed or high-pregnancy (i.e. particularly "wide") female wolves, single tracking can become more or less like double tracking. The same applies to the gait of our domestic dogs: heavy or broad breeds with short backs always double track. For example, for the German Shepherd and the Samoyed, the Siberian Husky or the Eskie, single tracking is the rule and is also required in the respective standard [7].

Why do land predators single track?

The wolf “single tracks” because it has to be able to trot for long periods in search of prey. His gait must therefore be very targeted, efficient and ergonomic.

Single tracking is much more energy-saving than double tracking: if a dog's legs come together under the body on a center of gravity when trotting, the dog can maintain its balance better, since not all of its paws are in contact with the ground at higher speeds. Single tracking allows the dog to reduce the sideways sway of his body and to stabilize it by creating a central center of gravity. The faster a single tracking dog moves, the more efficient his running style becomes. By the way, it only single tracks at higher speeds, and the Wolf doesn't single track when walking.

The shape and length of the runs influence a dog breed's tendency to "single track". The wider the dog is built and the lower his center of gravity, the more he tends to straddle; he trots (if at all) in a "double-track" manner. Since Double Track is not a very efficient running style, the result is that stray dogs tire much more quickly at high speeds because they have to run with much more effort.

The left dog single tracks, the other dog double tracks.

Picture 1: Trotting German Shepherd Dog: front and hind legs are in line; Picture 2: Trotting Spitz: the hindquarters touch the ground outside the forequarters; Image 3: Trotting wolf: front and hindquarters are in line; Picture 4: Trotting Spitz: the hindquarters rest on the ground next to the imprint of the forequarters.

The physique of the German Spitz does not correspond to that of the American Eskimo Dog

Since the American standard requires the American Eskimo Dog to be able to trot persistently in "single track", this allows initial conclusions to be drawn about his physical condition. This must therefore be strikingly different from that of our restricting Giant Spitz. The American Eskimo Dog is built sometimes differently, otherwise sustained trotting at high speeds would not be possible for him. The correctly built German Spitz, on the other hand, usually hardly trots because its square build means it is unable to run efficiently. The short back means that the animal in question tends to gallop rather than trot (most of the time, Spitzes trot only briefly and then gallop straight away), since at higher speeds the shocks when landing are less absorbed by the stocky body structure. As a result, this running style is very inefficient, and the dog does not have a sustained performance.

3.2) Different hindquarters

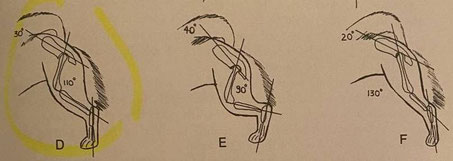

The American standard for Eskies requires that their hindquarters have to be “well angled”, the optimal angle being approximately 30°. In the graphic on the right, the desired position of the Eskie's hindquarters corresponds to panel D, while the hindquarters of the Giant Spitzes, which according to the German standard, can only be "moderately angled", corresponds to panel F. The hindquarters of the Giant Spitzes are much steeper than those of the Eskie.

And what does the angulation of the hindquarters mean?

The more angled the hindquarters are, the better and longer a dog can jump and run. Now, according to the official standard, our Spitzes have a rather straight, steep hindquarters. This type of hindquarter is desirable in some dog breeds and means that the dogs can stand very “stable”; the legs almost look like strong pillars.

This body structure is difficult for the dog's drive dynamics because “suspension” is not very possible. Some breeds - like the German Spitz - show an astonishing acceleration due to their pelvic tilt and sprint incredibly quickly, but not with any endurance. The dog also needs a certain “spring dynamic” to have the strength to jump off, which works better if there is more angulation. The same applies to sustained trot or extended canter: here too, a pronounced hindquarter angle improves endurance performance immensely.

Medium-sized dogs with steep hindquarters - such as the Spitz - always take a certain risk when jumping excessively, as it is very difficult to transmit power here. In particular, jumping from a height above the withers becomes more strenuous. This “effect” is not only due to the bony “ground substance”, but also to the fact that there is less “surface area” available for muscle attachment. At this point, this would also be a plea AGAINST agility in the German Spitz up from a certain (large) size! Because of his body type, the jumping practiced there is not good for his building.

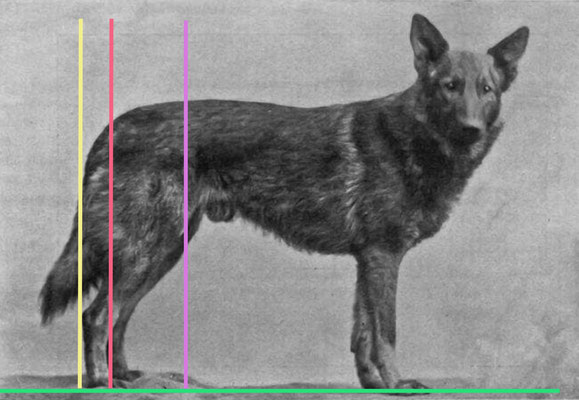

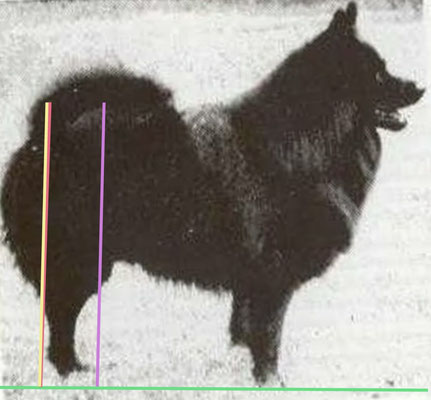

Picture 6 (German Shepherd) and Picture 7 (German Spitz): the sicklebone-like position of the rear metatarsus is marked in yellow. Once this line (yellow) is found, a second line is drawn that goes through the ischial tuberosity (red). With a third line that runs directly at the end of the loin, we can then see the “depth” of the thigh – here purple. With a steep angle like in picture 7, it can happen that the yellow line ends up in or even in front of the hind paws. Completely in contrast to a normal to large angulation: the yellow line is always behind the other two lines. Picture 8 clearly shows the excessive angulation of the Black Spitz's hindquarters. This corresponds more closely to picture 9 (German Shepherd Dog).

Conclusion?

The different angulation of the hindquarters required by the German and American standards for Giant Spitzes and Eskies once again clearly show that they are different. One was bred for endurance trotting and physically adapted over time, the other is not at all suitable for endurance performance due to its use and the resulting physique.

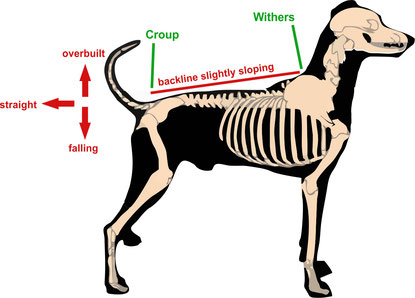

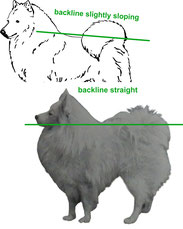

3.3) Different back lines

The main job of the hindquarters is to push the dog forward. It initiates every movement. By stretching the joints and pushing off the ground, the body is pushed forward. If the length ratio of the individual bones is correct, long, strong muscles with a lot of lifting height can be attached, the hindquarters have a large stride width and jumps, and the movement can be cushioned smoothly.

If the hindquarters (croup) are on the same level or slightly higher than the withers, the dog's back line is "straight" or "overbuilt". For example, shepherd dogs like the Šarplaninac - i.e. dogs that, like our Spitz, are stationary guard dogs - often show a slight "superstructure". This has its reason for the use of the dogs: in the past their task was protecting and guarding, and they were bred for strength and size and as a result lost the ability for sustained trot, which they did not need in their guard duty. On the other hand, powerful lunging at the opponent and sometimes even briefly pursuing him in the hardest possible gallop became necessary. This became necessary, achieved by a straight to slightly overbuilt back line.

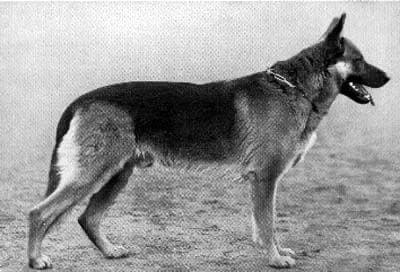

The American Eskimo Dog standard, on the other hand, requires that the withers be the highest point of the back line [10], which means that the Eskie's back line must always be slightly sloping. This definitely makes sense for him as a trotter, while the Spitz's straight to slightly built back line is ideal for his job as a farm guard.

By looking at the gait, the hindquarters and the backline of the Spitz and Eskie, the following can now be clearly concluded: the American Eskimo Dog is physically completely designed to move as persistently as possible at a regular trot. He is more athletic. The German Spitz, on the other hand, is a loyal guard whose entire physical appearance primarily serves to appear as impressive as possible in order to scare away predators of all kinds. In addition, he needs a lot of force when jumping and the ability to gallop sharply in order to be able to get there as quickly as possible and to be able to attack violently if necessary.

4.) The connection between body structure and hunting drive

The current standard for the German Spitz states that he lacks the hunting drive. But why doesn't the Spitz hunt? On the one hand, because a real Spitz has no interest in hunting.

But be careful: if the Spitz hunts mice, rats and similar vermin, this does not fall into the category of “hunting drive”, but rather into the area of "predatory drive" (see my article “The nature of the Spitz”).

On the other hand - and this is really important - he doesn't hunt because his physical condition simply doesn't allow it. As we have already seen, his short, straight back, his steep hindquarters and his gait are precisely bred to a dog that is ideal for a stationary guard dog on a yard or a boat. The Spitz can sprint fast and hard, but not persistently.

It is not without reason that the old books on Spitz consistently advise against breeding with dogs whose backs are too long. This is what it says in “Der Deutsche Spitz in Wort und Bild" (The German Spitz in Words and Pictures): "His entire body structure makes it difficult for him to hunt [...]. Due to his short back, he lacks flexibility in his loins, and he cannot hold his tail firmly on his back "Use it to control its body while hunting; its short forelegs and hind legs, which are somewhat straight rather than strongly angled, also prevent it from poaching." [8th]

This once again confirms the findings. So you can see that absolutely nothing about the physical characteristics of the Giant Spitz is subject to chance. In order for our Spitz to cut a good figure as the farm guard "par excellence", it is essential to ensure that:

- the back is really short, and the body is square (also in female dogs)

- the back line is completely straight to slightly overbuilt

- the hind legs have a steep angulation (maximum 20°)

- his gait at higher speeds is in no way “single tracking”.

The Eskie, on the other hand, has a different body structure, more similar to that of the Nordic Spitzes (such as the Swedish Lapphund or Samoyed, all of which hunt). His longer back, his more angled hindquarters and his single-tracking gait make differ apparently from our Spitz. This is confirmed both in the standards and in the literature about the Eskie.

Therefore: Nothing about the Spitz's body structure is a coincidence! His lack of hunting drive, his nature, his exterior arises from an interplay of various physical and mental factors, which is why every little detail about him is of the utmost importance!

5.) Conclusion

Although our white Giant Spitzes were the ancestor breed of the American Eskimo Dogs, the two breeds have diverged greatly over time - both due to spatial separation and the cross-breeding of foreign breeds into the American Eskimo Dog, such as the Samoyed from Siberia, who is bred not only as a sled dog, but also as a hunting dog. And just like the Samoyed, the Eskie has a higher energy level and is very active - in complete contrast to the German Spitz. The Spitz also likes to move, but rather moderately, and copes well with it when there is less going on.

Physically, German Spitz and American Eskimo Dogs also differ from each other: the Eskies are persistent trotters, while the Spitz is less capable of trotting. They each have a different gait pattern, because while the Eskie begins to walk like a wolf at higher speeds, the German Spitz double tracks consistently. The Eskie also has sometimes a higher prey drive [1], while the German Spitz, according to the standard, must have no interest in hunting at all.

What also becomes clear here: the Giant Spitzes, which Eskies have among their ancestors, may need to be trained differently than an original Giant Spitz due to the Eskies' higher energy level, their enjoyment of movement, their prey drive and their reduced alertness. They are also - as descendants of circus dogs, from which their territorial instinct was logically bred out - generally much easier to train, much more sociable with strangers or, for example, enjoy playing fetch games that would only cause reluctance in a German Spitz (retrieving originates from the hunting drive, so Spitz don't really retrieve). As a result, they are no longer suitable as reliable guard dogs.

In this respect, my advice: if American Eskimo Dogs are among the closer ancestors of your Great Spitz, take a close look at your dog. If he leans towards Eskie, then the Spitz training tips are not for your dog. He also most likely needs more exercise and activity than a regular German Spitz.

What is past can no longer be changed! This also applies to the numerous offspring of the two Eskies bitches that have been imported since 2003. The Spitz-Eskies that have already been born, on the other hand, would have to be looked at very closely and, in the best case, subjected to a working test adapted to the Spitz, in order to only use those that are genetically like the Giant Spitz for further breeding, so that the German Spitz population can increase again can get closer to the old ideal and the binding (!) standard. After all, our Spitz is an old German cultural asset that must be preserved at all costs!

6.) On my own behalf

I would like to make one thing clear: I have absolutely no problem with the American Eskimo Dog, nor against its descendants in Germany! I don't want to point fingers at anyone, but mistakes from the past have to be recognized and named in order to be able to correct them. Or, as Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach once wrote: "Eine Erkenntnis von heute kann die Tochter eines Irrtums von gestern sein." (An insight from today can be the daughter of an error from yesterday.)

No dog is better or worse than the other. But if you want to breed Giant Spitzes, then the pedigree shouldn't just say "Giant Spttz". Unfortunately, we now have more and more large Spitzes that neither meet the standard in terms of body nor nature. This means nothing less than that as a buyer, you no longer know what kind of dog you are actually getting. Will the Spitz be alert? Does he poach anything that moves? Is he 45cm shoulder height or more like 60cm? Do I have to brush every day or never? Does he love everyone, or does he prefer to bite strangers?

There are now also people who are of the opinion that the German Spitz of the 21st century has simply “modernized” and adapted to the times and demand. Because the "modern" buyer wants a Spitz who runs persistently on a bike, can keep up on very long mountain hikes, trails with enthusiasm and likes to be petted by strangers. This jack-of-all-trades is then only a German Spitz in name.

Our German Spitz differs from all other Spitz primarily in its lack of hunting drive. This lack is made up of various components, namely mentality and physical structure. So in the best case scenario, the German Spitz is not only not interested in hunting, he can't do it either. This is ensured by the short back, the straight back line, the steep hindquarter angulation and the short forequarters. An interplay of many factors, not one of which is irrelevant! The price you have to pay for this non-hunting dog is its lack of endurance, i.e. its unsportsmanlike nature.

If you still want to have a German Spitz with which you can really do long distances on your bike: there are plenty of other Spitz in FCI Group 5 that are sporty. For example, the Samoyed, the Lapphund or the Akita. It doesn't have to be a German Spitz! I think it's pretty crazy to bend it and breed it based on a personal wishful idea. Because the proper German Spitz was and is a pure farm dog, a primitive guardian according to old standards who would defend his master and his property with his life if necessary - and not a fluffy care bear from a little girl's imagination who would like to be petted by everyone, who never barks, who likes to pick cheese out of tree bark and loves ball games.

Despite all the prophecies of doom, there is still work for our German Spitz, because there is always something to guard. Times aren't exactly getting more comfortable, so you can be happy to have a dutiful and non-hunting guard at your side. Even if he doesn't want to run 10 kilometers at a relaxed trot on the bike. 😉

7.) Giant Spitz and American Eskimo Dog: A tabular overview of both breeds

| GERMAN GIANT SPITZ | AMERICAN ESKIMO DOG | |

| Crossbreeding | --- |

Samoyed, Japanese Spitz, Volpino Italiano and Dansk Spitz crossed |

| Head | Fox-like and triangular, with a slight cheek base | broad, slightly crowned, softly wedge-shaped |

| Eyes | medium-sized, elongated and slightly slanted (almond-shaped) | not quite round, slightly oval and widely spaced |

| Ears | triangular, as small as possible and set high close to each other | far apart |

|

Muzzle |

not too long and not too short, always in proportion to the top of the head (2:3), not blunt | wide, rather medium length in proportion to the skull |

|

Neck |

medium to short | medium length |

|

Breast |

deep and wide | deep and wide |

|

Paws |

as small as possible, rounded, pointed, with arched toes (cat's paws), sole color matches that of the nose | compact, oval, well-haired, dark pads and white claws, the toes are close together |

| Hindquarters | only moderatly angled | well angled (30° to the horizontal) |

| Croup | straight or slightly overbuilt | slightly sloping (withers is the highest point of the top line) |

| Color | all | white, biscuit |

| Body | square (1:1) | compact but not stocky (1,1:1) |

| Urge to move | needs moderate exercise | needs a lot of exercise |

| Gait | double tracks at higher speeds | single tracks at higher tempo |

|

Pace |

With good thrust, straight, fluid and springy. Gallops rather than he trots at higher speeds | trotting breed. Fast, efficient, persistent and powerful. Good reach in the forequarters, coupled with a strong hindquarter thrust when trotting |

| Hunting drive | no hunting drive | higher hunting drive [1], especially towards smaller animals (the Eskies were used, among other things, to hunt squirrels [5]) |

| Keeping with other pets | no problem | sometimes difficult due to the high prey drive, especially if the other pets are smaller |

| Nature | attentive, lively and exceptionally affectionate to its owner, intelligent, natural distrust of strangers | attentive, friendly, affectionate, intelligent, in need of communication, high energy level |

Sources:

[1]: www.orvis.com/american-eskimo-dog.html

[2]: AED Report

[3]: www.ukcdogs.com/american-eskimo

www.images.akc.org/pdf/breeds/standards/AmericanEskimoDog.pdf

www.caninechronicle.com/current-articles/breed-priorities-the-american-eskimo-dog/

[4]: www.naeda.org/2020/01/11/eskie-essence-and-instincts/

[5]: "The complete American Eskimo", Barbara Beynon, Howell Book House New York, ISBN: 0-87605-013-5, Seite 83

[6]: www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk8836/files/media/documents/AED_May_2021_Report.pdf - Seite 13

[7]: www.images.akc.org/pdf/breeds/standards/Samoyed.pdf

www.baxterboo.com/fun/a.cfm/meet-german-shepherd-dog/

[8]: "Der Deutsche Spitz in Wort und Bild", p. 65

[9]: With kind permission from ©www.sanjavonderhausbergkante.de

[10]: www.ukcdogs.com/american-eskimo, siehe "Body"

"Der Schäferhund in Wort und Bild", Rittmeister von Stephanitz, 1921

"Die deutschen Hunde" Part I & II, Richard Strebel, 1904

"Der Deutsche Spitz in Wort und Bild", Fachschaft für Deutsche Spitze, 3rd edition 1937

07.02.2022