History of the German Spitz

From antiquity to the 19th century

Preface

If you look at the history of the German Spitz, you are faced with the same situation as with many other dog breeds: the starting point was the mishmash of breedless farmer's dogs and local breeds, from which today's breeds emerged in the 19th century. That's why it's quite sobering to research a centuries-old history of German Spitz, because you can't really find much now. And what you find has largely been copied from each other.

But one thing is certain: despite all the prophecies of doom, the Spitz has not been killed over the centuries and has stubbornly defended itself against all exaggerated breeding shenanigans. That's why the Spitz on the ancient reliefs still looks like its modern colleague on the Urban Monument in Stuttgart, at the feet of a Swabian winegrower. May he stay with us for a long time!

From wolf to dog

Around 100,000 years ago, the distinction between the wild animal wolf and the domestic dog probably took place. The oldest Central European find currently referred to as a dog skull comes from the Goylt Cave in Belgium from around 31,700 BC. This is probably not yet a domesticated animal but rather a transitional stage in the sense of taming. In summary, the archaeological finds indicate that it must have been a popular pet in prehistoric times. Incidentally, the dog is the only domestic animal whose taming and domestication already took place in the cultures of the late and post Ice Age hunter-gatherer communities.

In the past, it was assumed that wolves were self-domesticating at people's campsites, and these animals were said to have fed on their hunting waste. However, according to today's teaching, it is more likely that young animals were specifically raised, which were then tamed through the process of imprinting (possibly wolf pups were suckled at the breast by women) and gradually separated from the surrounding wild wolf population. Bone remains that can clearly be identified as dogs come from a common burial site for dogs and humans in Bonn-Oberkassel from the Late Paleolithic (approx. 13,000-9,000 BC). Here it can be assumed that there is a firmly established human-dog relationship and thus domestication.

First dog breed breeding

There are particularly numerous dog bone finds from the early Holocene; The dogs were probably used as hunting assistants, and some of them were also used for meat. The animals were medium to large and had a shoulder height of 45 to 60 cm.

From the Stone Age onwards, the variety of forms of skeletal finds increased, the height of the animals varied from 32 to 60 cm and one can already assume that the dogs were used for a specific, functional purpose as hunting dogs, herding or driving dogs, as well as guard and farm dogs. A medium-sized dog type is particularly common here, the so-called "Torfhund" or "Torfspitz" (Canis familiaris palustris Rütimeyer, "Peat Dog").

Significant changes and variety of skeletal forms in the sense of a functional 'dog breeding' were only observed from the Roman imperial period onwards. In addition to medium-sized and large animals, small dogs can now also be detected; the shoulder height variation ranges from 18 to 72 cm. The first indications of targeted pedigree dog breeding also come from Roman culture; an example would be the Molosser.

Skeletal finds from Germanic settlements mainly show medium to large dogs (45 to 67 cm) of the wolf-like type, similar to our present-day German Shepherd Dogs, Collies and Wolfspitzes.

In the European High and Late Middle Ages, a similar variety of forms as in the Roman Empire can be documented. The skeletons of smaller dogs have been found in castles and cities, while medium to large dogs still dominate in rural settlements. Evidence of the first beginnings of pedigree dog breeding comes from urban settlements and is supported by the increasing number of contemporary illustrations from the high and late Middle Ages. However, true dog breed breeding (according to certain external and character traits) only emerged in modern times.

Torfhund or Torfspitz?

Spitz enthusiasts like to attribute the breed an age of 5,000 years or more, citing Rütimeyer's bone discoveries in pile dwellings in Switzerland and southern Germany. However, the peat dog was only really researched under Professor Theophil Studer in Bern. He wrote: "In the pile dwellings of the Neolithic period, different breeds of dogs can be found, depending on their size and shape. The most common form was that of a fairly small animal, the size and shape of a medium-sized Spitz." This meant that the dog that Rütimeyer had called the Torfhund (Canis familiaris palustris Rütimeyer, "Peat Dog" became the Torfspitz and, in the eyes of researchers, the first and oldest pedigree dog in Europe. For many today, the German Spitz remains the direct descendant of the small dog of the pile dwellers from the Neolithic period. This opinion was supported by Studer's "Family Tree of Dog Breeds" from 1901, in which the Torfhund was identified as the parent form of all today's Terriers, Pinschers and Spitz.

A lot of criticism was leveled at Studer's family tree because dog breeds can only be differentiated to a limited extent based on skull finds. More detailed examinations showed this, as the skeleton and skull of today's Spitz are quite different from the Torfspitz. Genetic similarity is also not sufficient to assume a clear coordination between the races. The Spitz friend definitely has to say goodbye to the beloved picture that shows the Wolfsspitz in front of the pile dwellings that have to be guarded.

The different appearance of the dog skulls found in Rütimeyer's Stone Age cultural layers also led many researchers to assume that not all dog breeds descended from wolves. Konrad Lorenz, for example, assumed that only Chow Chows and the Spitz breeds descended from wolves; in his opinion, the golden jackal was the ancestor of all other breeds. Despite its popularity, this approach was wrong because molecular genetic studies have now shown that the wolf alone is the ancestor of all our domestic dogs.

The Spitz until antiquity

Nevertheless, Spitzes are without a doubt an ancient form of domestic dog. Not as a breed in the strict sense, but as a type. They emerged wherever dogs were kept - as a primitive form, so to speak - and certainly had a more historic past than most other dog breeds. The dog that we now call the "German Spitz" only really became tangible in Ancient Greece. Several very pretty depictions of Spitzes on objects such as coins and jugs survive from this period. The dogs pictured would still easily pass for Spitz today, because they not only have curly tails and erect ears, but also longer fur and are always shown in "companion dog situations".

One of the few names of ancient dog breeds that we can really interpret (the Melitäer = Maltese) is, as Otto Keller showed in his book "Die antike Tierwelt" (The Ancient Animal World), a Spitz, although not identical to the modern breed of the same name. However, the pictures show how little the Spitz has changed over the centuries. The curled tail, for example, must have been a domestication feature that appeared very early, because the paintings in ancient Egyptian tombs show dogs that closely resemble the Pharaoh Hound, and other smaller, short-haired dogs.

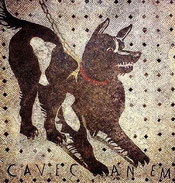

The Pompeian domestic dog, the actual Cave Canem guard dog, probably corresponded to the Spitz. However, there is no evidence that this dog could have come from the south.

In any case, Spitz-like dogs appear very early wherever dogs were kept and bred as domestic dogs. They were widespread and were used for various tasks: they were farm and field guards, herding dogs, sled dogs and were and still are hunting dogs (Finnish Spitz, Elkhounds, Laiki). Just the German Spitz is the only Spitz-like species that has no hunting drive. The original dog types are all similar to the character of our current Spitz. They live in a certain independence from humans, and at the same time they were useful for everything and nothing.

Does the Spitz come from the north?

The myth of the Nordic origins of lace goes back to Ludwig Beckmann, who was of the opinion that Spitzes came from Scandinavia to the Baltic Sea coast and from there to Pomerania in carts. He was obviously not aware of the different character of the German Spitzes in contrast to the Nordic Spitzes. The Laika dogs (Elkhounds, Finnish Spitz and also Samoyeds) were and are hunting dogs in their homeland, while the European Spitz is said to lack any passion for hunting. Richard Strebel, on the other hand, saw the Spitz originating in central Germany, from where it spread to the north and south.

However, it was probably the case that there was a basic form of the Spitz in the Northern Hemisphere that was widespread there. Over the centuries, regionally adapted variants of the Spitz were bred from this original Spitz. This would also explain the visual similarity between the different Spitz breeds, which sometimes have major differences in temperament and behavior.

The problem we encounter here is ultimately the same as with other dog breeds: The starting point for the German Spitz as a breed were the breedless farm dogs in the past, from which today's pedigree dogs were formed in the 19th century. Therefore, it is basically pointless to research the history of Spitz that dates back centuries or even millennia.

From antiquity to the 18th century

After the representations and portraits of Spitzes in Ancient Greece, the "Dark Ages" begins. For over a millennium nothing, at all, can be found about the Spitz; he disappears for centuries, only to reappear in modern times. In the Middle Ages, the Spitz was one of the most widespread dog breeds and was virtually omnipresent in Central and Northern Europe. Despite its widespread popularity, the Spitz received little attention as a dog of the common people and was therefore rarely depicted.

The Spitz can certainly be viewed as a kind of ancestor of various dog breeds, which were subsequently adapted to the respective climatic conditions of their environment. In the colder climates - with correspondingly lower population densities - dogs were needed, such as the Samoyed, who guarded, drove the reindeer herds, pulled the sleighs and also acted as humans' hunting assistants. In Germany, however, hunting was an exclusive prerogative of the nobility. If farmers or ordinary citizens kept dogs suitable for hunting, they had to be made unsuitable for hunting, for example by cutting off a barrel or wearing a thick wooden stick around their neck. For this reason, the German Spitz was created in Germany at that time, who had no inclination towards poaching and hunting.

About making the dog unfit for hunting, we learn from the glossaries that the expression “canem expeditare” (to prepare a dog) in the forester's language meant trimming a dog's paws in accordance with the forestry laws so that the dog wasn't able to poach successfully. The English called this operation “Lawing of Doggs” and it happened there in two ways; namely, either by cutting off three claws, namely the claws on the right forefoot, on the outermost part of the toe close to the skin, or by cutting out the ball of the foot, which was called “the bat of the foot.” This method of preparing dogs was devised in the second half of the 12th century and was first prescribed in the 6th article of the Woodstock Forest Laws, where the expression “espeditatio” (preparing) was used for the first time; where it says: "Item rex praccipit, qnod escpeditatio mastivorum fiat, ubicumque ferne suae pacem hahent vel habere consueverunt." (Those who lived in the forests were obliged to pay a fine of 3 solidis and 4 denarii, which fell to the king, if they do not keep their Molossians and all other large dogs in the prepared way and this preparing was to be renewed every third year in accordance with those laws.)

The interested reader can read almost everywhere about the famous house rules of Count Eberhardt of Sayn (1425 -1494), in which the word "Spitzhundt" (Spitz dog) appeared for the first time.

In it, the count forbade his household servants from insulting each other as “pointers” and subjected them to strict punishment. “Spitzhundt” was apparently a rude insult at the time, which suggests that the Spitz was probably not held in very high regard back then. Even into modern times, yapping Spitzes were often compared to nagging women.

The Middle Ages were followed by the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), which also shaped the entire 17th century. This war, which completely devastated the German Empire at that time and decimated its population, brought about a huge regression in all areas of life, including literature. There are almost no reports of any dogs. The approximately 8 million Germans who survived understandably had no interest in this regard. Since cannibalism is even reported from individual testimonies about the conditions at the time, it can be assumed with great certainty that almost no dog survived, but the remaining animals almost certainly ended up in the cooking pot.

First mentions of the Spitz

For the first time, the specialist cynological literature that emerged around 1800 went back to the Spitz. Krünitz mentioned the Spitz for the first time in his “Oekonomische Enzyklpädie" (Economic Encyclopedia) in 1773. The dog described by Buffon in 1772 as "Chien Loup" (German translation: "wolf dog") was described in 1800 by Sydenham Edwards in the "Cynographia Britannica" - referring to Buffon - as "Pomeranian" or "Fox Dog". We find a similar description in the "Sportsman's Cabinet" from 1804. Here the predominant color is cream or pale white-yellow with a lighter undercolor. White and black Spitzes are also mentioned, and piebalds are mentioned as rare. A description published in France by Gayot (1867) distinguishes the white variety as "Louploup d'Alsace" from the wolf-colored "Chien de Pomeranie". In 1836 Dr. Ludwig Reichenbach describes the Spitz in his work "Der Hund in seinen Haupt- und Nebenraçen" (The Dog in its Main and Secondary Breeds), which clearly places him among the original dogs.

Bechstein also reported on the Spitz as early as 1793 in "Getreue Abbildungen naturhistorischer Gegenstände" (True Illustrations of Natural History Objects). In 1809, August Goldfuß described the Spitz in his „Vergleichende Naturbeschreibung der Säugethiere“ (Comparative Natural Description of Mammals) as the most important representative of domestic dogs ("Canis familiaris") and already listed various Spitz breeds with their different uses.

In 1934 "Lexikon der Hundefreunde" (Lexicon of Dog Lovers) - as with Krünitz - the opinion is expressed that the Spitz got its name because of its pointed muzzle and pointed ears. Whether this interpretation is correct? Hardly likely. Other dog breeds also have these characteristics. In any case, it is certain that in the Middle Ages the name of the large farm dogs was "Hovawarth" (Hof-Wart: farm guard) and that of the small farm dogs was "Mistbella" ("Der auf dem Mist bellt" - which barks on the dung - dunghill barker). These small guard dogs were apparently not called “Spitz” back then, although you could see them as a Spitz-like dog.

The fact that the German Spitz was not mentioned at all for centuries may be due to the fact that it was so widespread, well-known and common that it was not considered worthy of immortalization. It remained the people's dog throughout Germany until the 20th century, i.e. the dog of farmers, carters, traders and boatmen. For all of them, the Spitz was indispensable as a reliable companion, alarm system and playmate for the children, as well as for catching rats, driving cows and herding geese. Just like the Spitz, these people disappeared into the darkness of the centuries; they were without history and yet indispensable.

The oldest name for the German Spitz was “Pomeranian”. The fact that the word Pomerania appears again and again in connection with Spitzes does not mean that all Spitzes originally come from Pomerania, but in Pomerania it was only the breeding of beautiful white Spitzes that flourished. Echoes of this can also be found in the English "Pomeranian", in the Swedish "Pomerska Spetsen" and in the French "Loulou de Poméranie" and "Chien pomérien". Something similar can also be found with the so-called “Mannheimer”, the black small Spitzes.

In “Naturgeschichte der Stubentiere” (Natural History of House Animals), Bechstein divided the Spitz into several classes: the domestic dog (“Canis Domesticus”) or Spitz (“Heidehund”, “Pomeranian”), the short-haired Spitz, the Fuchsspitz (“Wiesbadener Spitz”) and the Wolfhound (white Spitz). Back then, our current Spitz was called, among other things, “Wolf dog”. He was the most common of all dogs and was seen everywhere in the villages - especially in Thuringia - as the farmers' favorite dog.

Buffon referred to the Spitz as “Chien Loup,” while Haller also called him “Wolf dog.” It was first referred to as “Spitz” by Schreber in 1778, although all terms basically mean “Canis Pomeranus”. In 1773, the Spitz was called “Pomeranian” for the first time by Linnaeus. Most likely, since Linnaeus completely ignores the Spitz in his description, he had the Spitz itself in mind as the domestic dog - "Canis Domesticus". Bechstein also wrote “Domestic Dog or Spitz” as.

This shows that the Spitz was always seen as the domestic dog - so he was the epitome of the ordinary domestic dog, the epitome of the people's dog. Back then, the dark animals were used as guard dogs for the yard and farm so that they would not be seen by thieves. White ones were preferred as herding dogs so that wolves could not recognize them among the livestock.

In older books, the Spitz is also called “Heidehund” or “Haidehund” ("Heide" means "Heathen", Spitz as the dog of the heathens). Whether this points to an old tradition regarding its origins or rather to gypsies who carried him with them is unclear. Gypsies used to be popularly called Heiden or Haiden, and to match this there was a Spitz-like "Gypsy dog" that was also called "Haidhund".

Müller also called the Spitzes “Danziger dogs” or “Pomeranians”. In 1781, the Englishman Pennant recorded the “Pomeranian Dog” for the first time. Borowski, Bechstein, Halle, Graumann and Künitz later referred to him as a Wolf dog. In Switzerland our Spitz was probably also called "Pummer" or "Pommero", which was the name used by Germans, Italians and Rhaeto-Romans alike.

A mostly white-colored sheepdog from Pomerania, has been mentioned in literature until recently as the “Pomeranian Spitz” or "Pommerscher Hütespitz". In any case, the fact is that around the year 1700 these white herding Spitzes were very common in Pomerania, and it was therefore assumed that the white herding Spitzes originally came from Pomerania. It is noteworthy that the color white was apparently a preferred color in Pomeranian breeding across all dog types.

By the way, the transitions between the breeds were sometimes fluid, because until the end of the 19th century it was not really possible to distinguish between sheepdogs and Spitz. The name “Hütespitz” (herding Spitz) also reminds us of this. For the animal painter Friedrich Specht (1872), the German Shepherd Dog was primarily a Spitz dog.

The Keeshond as a symbol

The Wolfspitz (Keeshond) was the symbolic figure of the Patriot Party in Holland at the end of the 18th century, while the Pug represented the opposing Orange. At that time, it was fashionable to trim the Wolfsspitz like a poodle. With this strange silhouette you can find him on political pamphlets, engraved glasses, etc.

One reason why the Wolfsspitz served as a political symbol for the idealistic fighters against absolutism was the well-known vigilance of the Spitzes. Vigilance in the event of violations of the relentlessly demanded republican virtues was an absolute necessity, the neglect of which was punished by the incorruptible Robespierre with the guillotine after the French Revolution of 1789. However, unlike the French, the "Keezen" (the patriots) made a "soft revolution". The Dutch constitution, the original form of which was essentially formulated by Cornelis "Kees" de Gijselaar, ultimately gradually realized the principle of popular sovereignty.

The Spitz in England

Queen Victoria of England with her Pomeranian dog "Gina"

In the 18th century, the 17-year-old Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz married the future King George III of England. She had white Spitzes from Pomerania delivered to the English court. Today's Pomeranians were bred from them in the following decades. Under George and his German wife, the breed eventually became the favorite of the noble houses. It is to this fact that we owe the beautiful, elegant depictions of Spitzes in the paintings of Stubbs and Gainsborough. However, the Pomeranians only achieved their high level of popularity under Charlotte's granddaughter, Queen Victoria of England. In 1888 she discovered the Pomeranian, but not in her native England, but during a trip to Italy. In Florence, she bought several Pomeranians, including the famous Marco and the bitch Gina, who appears in the video below.

The adjacent portrait of Mary Hill was created in England around 1820 and shows that our Spitz was already a favorite of noble circles there over 200 years ago.

At this time, Pomeranians were no longer found exclusively in aristocratic circles, but were also becoming increasingly popular in other social classes and were eventually bred in the USA. Little by little, Spitzes under English breeding became smaller (the size roughly halved over time) and more toy-like.

Nevertheless, the Spitz does not go down well with some English scholars and Sydenham Edwards, for example, amazes with his disparaging assessment of the Spitz, writing in the "Cynographia Britannica":

"He is of little value because he is noisy, scheming and quarrelsome, cowardly, stubborn and treacherous, likes to snap, is dangerous to children and is of no use in other respects... So he lacks useful qualities and is not even affectionate." However, it would be "pretty difficult to steal him". Well, at least that’s what the slanderer admits!

Perhaps the tirades against the Spitz can be explained by an aversion to foreign dog breeds, which are not suitable for any special tasks such as retrieving. However, this judgment is surprising, since the Spitz was so popular in England at times that the white Spitz became a fashion dog in London around 1900 - until it lost the favor of its lovers due to its restless and loud nature. But here, too, the popularity of Spitzes has admittedly fluctuated considerably over the centuries.

The small Spitz, which was called Pomeranian in England as early as 1890, was also known on the European continent under the names "Pommer", "Loulou", "Volpino", "Spitz" and "Vulpino". Eventually, the term "Pomeranian" was only used for the dwarf form, which was first shown at kennel club shows in England in 1871. The animals should weigh no more than 10 pounds, and any color was permitted. As early as 1905, 125 Pomeranians were registered at an exhibition. The breed was already registered with the Kennel Club at that time, while the Keeshonden were only recognized by the KC in 1925.

Fashion dog and outsider

Dog breeds are subject to fashion, and the Spitz could not escape this, and so its popularity varied considerably over time. There were years when they were almost “in vogue”, then again they were forgotten, but thank God they never completely disappeared. However, while the Spitz had previously been common, perhaps even the most common among farm dogs, it was noticeably displaced by other breeds towards the end of the last century. This can also be seen from various reports:

"30 to 35 years ago the large Spitz, whether black, white, yellowish or wolf-colored, was often a loyal guard on the wagon. Unfortunately, he has now been almost forgotten in his ancestral home," it says in 1921. "He used to be the most common dog in the districts of Cologne, Düsseldorf and Aachen, with three quarters of the Spitzes being of the wolf-gray variety. There was probably no farm or freight wagon in the past that did not have a Spitz as a guard, but now there is an excellent and purebred Spitz difficult to find..." wrote Jean Bungartz in 1884.

And 10 years earlier, Dr. Leopold Fitzinger said that the Spitz, which was one of the most common breeds in Central Europe just forty years ago, has now become quite rare and may be on the verge of disappearing.

The rarity of the Spitz is also mentioned in the "Buch der Hundeliebhaber" (Book of Dog Lover) published in 1876: "While we used to find these extremely attentive, watchful dogs very often in villages and cities and such dogs were rarely missing from a postal van, today they have become rare, although it is difficult to find a better guardian among small dogs who does not leave his master's property."

And although the Spitz could be found from St. Petersburg down to Italy and there were only a few breeds that were so widespread, for a very long time there were very few large-scale breeders of Spitz; in Germany, Switzerland and Austria together there are only a handful. The Wolfsspitz was mainly bred in the Württemberg Black Forest and Westphalia, the black and white Giant Spitz mainly in the Rhineland and Westphalia, and the Miniature Spitz - also known as Mannheimer Spitz - in southern Germany.

A true jack of all trades

In the countryside, the Spitz has been a reliable guardian since ancient times and, as the so-called "Mistbella" (dog on the dung), eagerly announced the arrival of a stranger. Because of its loyalty to its homeland, the Spitz is not interested in straying and poaching, which is why hunters in particular have turned to the Spitz - and especially the Wolfsspitz. Wolfspitz and Giant Spitz were even bred in individual regional associations of the German State Hunting Associations. This ensured that the owner got a cheap Wolfspitz if his poaching dog was shot by the foster. The German State Hunting Association therefore urgently recommended that its members carry out the systematic breeding of the Wolfsspitzes and supply as many farmers as possible with these extremely useful dogs.

Because Spitzes are small and maneuverable, they also fit into the narrow spaces of bygone times (such as ship cabins and covered wagons), when the rough carters were kings of the streets. So what the Stallpinscher once was in southern Germany, the Spitz was in the north of the country: it was the constant companion of the freight wagons - or "2 hp oat engines with whip ignition" - which transported goods over long distances before the age of railways. Here the Spitz had his duties as a guard over the goods being transported and as an exterminator of rats and mice in the horse stables. His owners thought highly of him; the others naturally less so.

As Fuhrmannspitz, he sat next to the coachman or made himself more or less comfortable on the load, or he was in a box that was suspended on chains under the wagon and rocked back and forth. If there was no room for him at all, he trotted along next to the car. In the 1880s, messenger carts were still traveling everywhere in Germany. In southern Germany, the black Spitz is said to have taken part, while in the Bergisches Land and the Lower Rhine the Wolfsspitze was also present. In the standard of 1880, the term “Fuhrmannsspitz” was even used as a synonym for the Wolfsspitz.

But the Spitz also cut a good figure as a companion to wandering traders (Kiepenträger) who traveled with their back basket (German: Kiepe). These wandering traders were usually farmers who traveled across the country with their goods at a certain time of the year and sold their products directly to consumers. And who would be better suited to accompany and guard those goods than the Spitz?!

Incidentally, these wandering traders developed their own trading language over time, namely "Krämerlatein" (colloquially: merchant's Latin). They used this language to communicate with each other on their journeys. However, when they met at home, normal Low German was spoken.

The monument to the Kiepenträger (Kiependraeger), created by Hubert Löneke in 1984 in the pedestrian zone in the heart of Breyell (Germany), is a reminder of the great importance of the wandering traders in the past. Of course, not far from the Kiepenträger, you will also find his Spitz. He is depicted in typical Spitz pose, attentive, with his front paw raised and facing his master.

With the advent of the railway, the wagons and their four-legged companions disappeared more and more, but the barges continued to serve the river for decades. The Spitzes were often planted like figureheads at the bow of the barges:

"Instead, they tend to bark and entertain themselves. Anyone who has ever observed the board dog on a Rhenish tugboat, which by tradition is always a Spitz, can confirm how nicely such a dog entertains itself when he speaks loudly about the waves overboard, the clouds, the distant railway, an airplane or something else."

These dogs were left on board to keep watch when the crew was on shore leave. No thief, no matter how quiet, would have gotten on board unnoticed.

In Schleswig-Holstein of the past, a more robust variety of the white large and medium-sized Spitz, which was also called "Schifferspitz" there, was also used to pull the carts of the scissor grinders. [11] Since so-called dog carts were still on the road until the 1930s - i.e. H. carts that were pulled by dogs - it can be assumed that correspondingly large Spitz were also used as pulling dogs. Because the dog was the poor people's cheap draft animal - and Spitzes were available on every street corner at that time.

The vigilance of the Spitz was not only evident as a coachman's dog or as a "Schifferspitz" (skipper's Spitz), but wherever there was something to guard and an attentive, nimble jack-of-all-trades was required. So German Spitzes protected not only farm, ships and wagons, they were also used to protect cemeteries and churches in the night. The local night watchman got a Spitz at his side, who was supposed to alert him to dangers and to protect him from attacks.

Still at the beginning of the 20th century, the "Urban Monument" in Stuttgart, which showed a winemaker with a Giant Spitz, was reminiscent of the "Weinbergspitz" (vineyard's Spitz), who had to drive away uninvited two- and four-legged visitors from the vineyards and even scared away the birds with his barking (the monument melted down after the Second World War, only a few pictures remain). The "Kuhhirtendenkmal" (cowherd monument) in Bochum, which was also melted down but re-erected in a true-to-original copy in 1962, shows a cowherd blowing his horn, with a Giant Spitz standing at his feet. In addition to all of his other skills, the German Spitz is also good at herding livestock.

Another job for the Spitz in old times was the “dog wheel”. For example, in the nail forges of that time, the dog ran in a kind of treadmill and thereby moved a bellows that generated the high degree of heat required to melt the iron. Gottlieb Schnapper-Arndt reports as follows:

"In a strange way that seems unlikely to the viewer, the air is supplied to maintain the fire. A smaller dog moves in a wooden wheel (around 1.6 meters in diameter), which has an iron crank on its axle. The breed of dog was usually a Spitz or a Pinscher; the crank is connected to a lever which sets a bellows (about 1.5 meters long and 1.2 meters wide) in motion." [10]

The photo on the left shows a cart on which an old, original nail machine is mounted and which is powered by a large, white Spitz. The cart was shown on the occasion of the parade of the 800th anniversary of the community of Arnoldshain. Similar treadmills driven by dogs were previously used in brandy distilleries, for example, to sprinkle water on the cooling coils of the stills.

In the southern German wine-growing regions, the black Giant Spitzes were particularly widespread, guarding the farm during the day and keeping watch in the vineyards at night (which is why they used to be called "Weinbergspitz"). Their field of activity extended not only to keeping human thieves away, but also to scaring away not only snacking birds but also predators such as foxes and badgers, who sometimes even risked their lives between the sharp teeth of the Spitz just to get to the sweet grapes.

I have been unable to find anything in my literature to support the theory that the black Giant Spitzes also drove wild boars out of the vineyards. Wild boars are not mentioned anywhere, so I am currently assuming that there is no truth to this claim...

The white Giant Spitz was actually always the typical guard of the farm and was also used to herd flocks of sheep. The white coat color is of great importance for a herding dog because it allows you to distinguish him from a wolf from a distance and at night. By the way, the white Giant Spitzes are usually a little more moderate than the large, black Spitzes. At the beginning of the 20th century, many white Spitzes were exported to France, where they were unfortunately crossbred with Samoyeds. For example, the French champion “Prince LuLu” came from this crossbreeding.

The Wolfsspitz forms his own group within the Giant Spitzes, because he is not only significantly larger (originally around 60 cm shoulder height) and more solidly built than the Giant Spitz, no, his fur also has a completely different structure. In terms of character, he is much more comfortable than the large Spitz, but also more stubborn. However, he is definitely not boring and when he gets angry, he does so like hell. Like the white Spitz, the Wolfspitz was also used primarily as a farm guard and herding dog.

[1] Gallo-Roman tombstone, 1st century AD; photo: Musée des Antiquites Nationales

[2] Zitat Hugo Dannacher in „Der Deutsche Spitz“ Nr. 16, Seite 9 f.

[6] Luttrell-Psalter. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 42130, fol. 70v. England um 1330-1340

[7] Luttrell-Psalter. London, British Library, Add. Ms. 42130, fol. 158. England um 1330-1340

[9] From Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

[10] "Der Hochtaunus - eine sozialstatische Untersuchung über die fünf Feldbergdörfer"

[11] "Der Deutsche Spitz" no. 92, p. 11

25.01.2024